It should be noted that this a very brief book in graphic novel terms at only 34 pages, but those pages have greater value than some entire ten volume series. Much of his repertoire remains in print, and all is worth investigating by the art lover. Has this impacted on his gorgeous art being under-appreciated? It’s to be hoped not. Other than early in his career, Russell’s never worked on material that makes hot 100 lists. It’s related more to the earliest versions of fairy tales recounted by the Brothers Grimm than the sanitised cheer we know today. What begins as straightforward takes a tragic turn as the nightingale, determined to help, learns of the one sure way of manifesting a red rose in winter, and the tale concludes with a flourish of casual cynicism. These were written long before Disney’s cinema rendered this common currency, and even as talented an artist as Russell depends to some degree on the Disneyesque form in humanising his plants and animals.

It’s a variation of a formula used throughout his fairy tales of nature commenting on human wisdom or folly. Wilde casts the nightingale as the adjudicator of honest love, which is the emotion worthy of its song. This is overheard by a nightingale and the plot is in motion. His love will dance with him if presented with one, but he has none. The Nightingale and the Rose begins with a beautifully pastiched fairy tale moment, of a lovelorn man in his garden bemoaning the lack of a red rose. Here’s a figure to hate, yet Russell also engages our sympathies via an almost beatifically smiling Hans.

Russell’s rendition of Hugh in all his finery is a monument to callous hypocrisy, with a permanently pasted smugness to his face. Beyond that, it remains a sad commentary on how the entitled see themselves. It’s pointed, heartbreaking and very funny. During the winter when Hans goes cold and hungry the miller’s justification for not inviting his alleged friend to share his food and fire is a desire not to induce envy as it would spoil his good nature.

There is, however, not a shred of reciprocation. Hans enjoys listening to the more erudite man expound on friendship, and doesn’t begrudge him the armfuls of flowers and herbs to which he helps himself from Hans’ garden. The former is the most blatant social commentary of Wilde’s fables, contrasting the wealthy and pompous Hugh the miller with Hans the gardener. They’re well matched, both bleak and with a broad cynical streak, yet very entertaining.

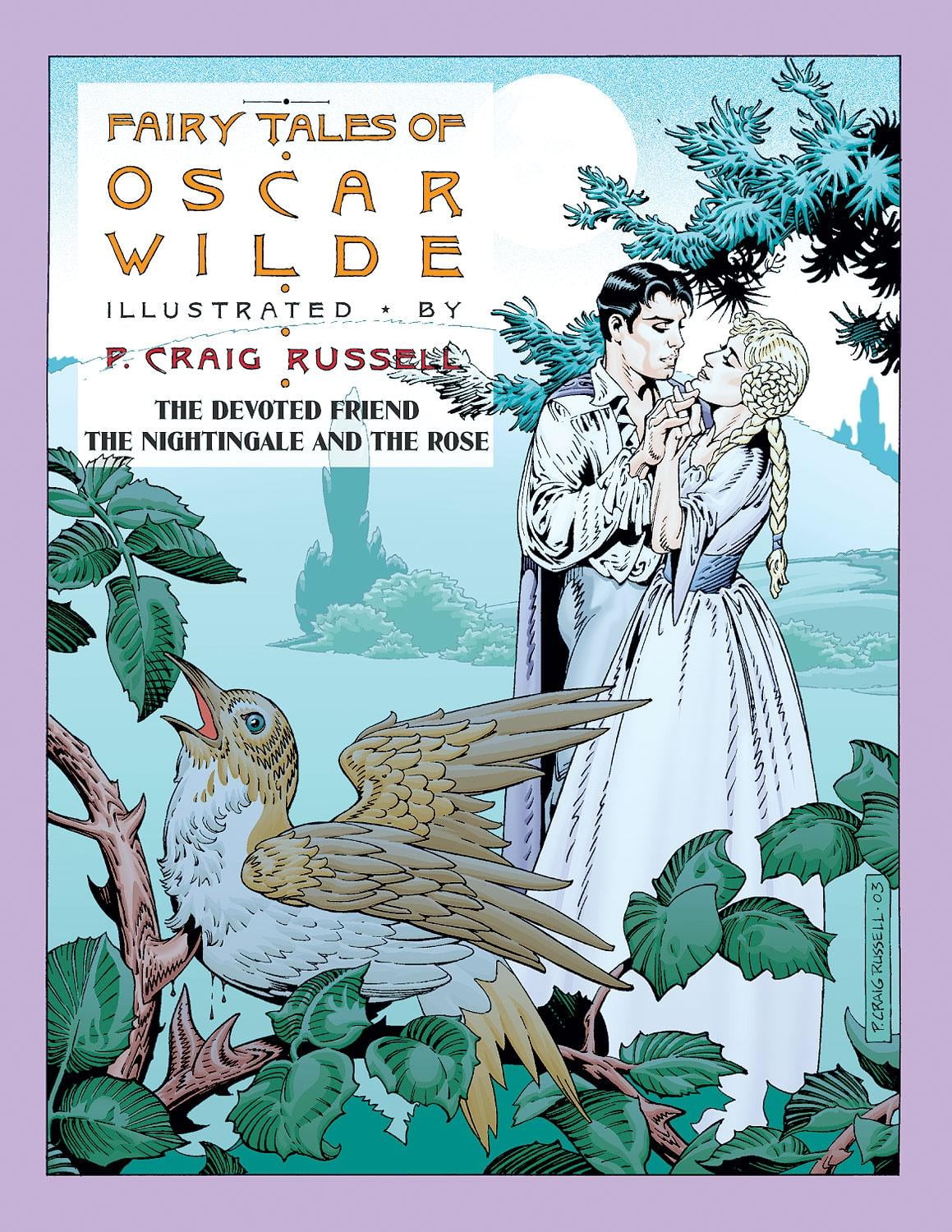

Artistically this has been a great success to date, and we’re here presented with The Devoted Friend and The Nightingale and the Rose. Craig Russell, six years after the last, indicated a plan to transfer them all to comic format. Oscar Wilde wrote nine fairy tales in total, and the appearance of this fourth graphic novel of adaptations from P.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)